40 Years Later, Lifeforce Is Still the Most Insane Would-Be Blockbuster Ever Released

When it comes to Halloween watches, film fans around the world have many classics to choose from. From John Carpenter’s Halloween, Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, or William Friedkin’s The Exorcist, to the various installments of beloved franchises like A Nightmare on Elm Street, Friday the 13th, or Scream, to newer entries like Jordan Peele’s Get Out, Coralie Fargeat’s The Substance, or Ryan Coogler’s Sinners, there’s a litany of riches for genre fans to discover or revisit every time spooky season rolls around. But if you’re looking for something different for your Halloween party this year, something that will make you wonder how it even got produced at all, look no further than the 1985 film Lifeforce, which 40 years after its release may still be the most bonkers big-budget film of all time.

Coming courtesy of director Tobe Hooper, who is better known for 1974’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and 1982’s Poltergeist, Lifeforce is an anomaly by any standard. It’s a movie about space vampires, featuring plenty of violence, nudity, and overt sexuality, all culminating in a zombie apocalypse in London, and somehow it’s even more bizarre and horny than you could possibly imagine. And it was made for comparable money to fellow ‘80s blockbusters like The Empire Strikes Back, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Ghostbusters and Die Hard. How did this happen? Is this movie even real? And why does it still have so much staying power among cult film enthusiasts to this day? Let’s take a look.

Brown-Eyed Space Girl

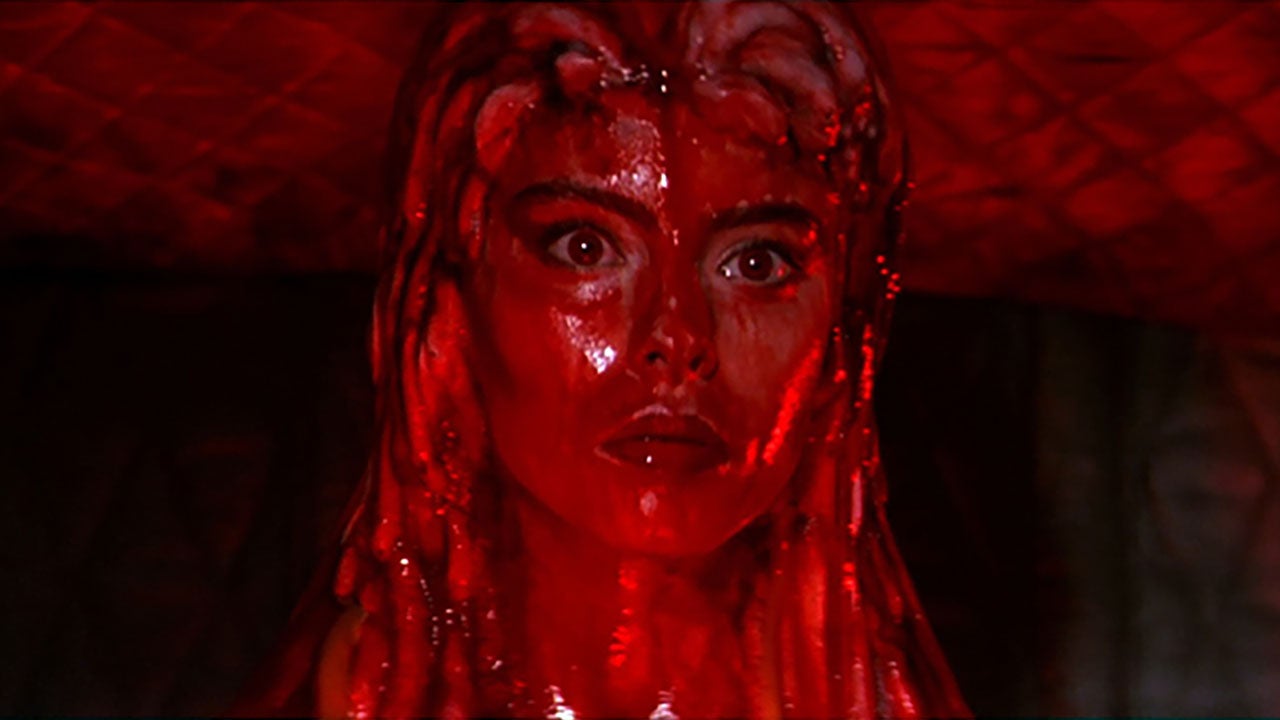

Adapted from Colin Wilson’s 1976 sci-fi novel The Space Vampires, Lifeforce opens with a group of astronauts aboard the space shuttle Churchill, who discover an alien spacecraft that looks like, well… a giant penis. Inside the craft they discover the desiccated corpses of bat-like aliens and three human-looking beings preserved in energy capsules. These would be the space vampires in question, led by Mathilda May in one of her earliest roles as the piece’s main villain, known only as the Space Girl. The vampires drain the life force (naturally) of the crew, leaving Colonel Tom Carlsen (Steve Railsback) as the only survivor. When Europe’s Space Research Centre recovers the wreck of the Churchill, they bring back the vampires to Earth, who subsequently break out and cause all manner of havoc.

Major highlights include Carlsen’s psychic connection to the Space Girl, who he is obsessed with even while trying to stop her, Peter Firth’s Colonel Colin Caine as the perpetually unfazed SAS investigator trying to ascertain how to stop the creatures’ destruction, and London becoming the staging ground for a cataclysmic finale as the full scope of the vampires’ plans come to fruition. It’s a movie that doesn’t just have twists and turns, but wholly reinvents itself genre-wise every 30 minutes or so. It starts as an atmospheric horror film set in space, then turns into something akin to a BBC detective drama, before ending as an epic zombie apocalypse film, while also weaving in elements of Gothic romance with the connection between Carlsen and the Space Girl. If you ever wanted to see what amounts to a gonzo Dracula adaptation that includes H.R. Giger and Lovecraftian influences and also copious amounts of bare skin, then this is the movie for you.

But Lifeforce is more than just its most outrageous elements. It has so much going on in terms of tone and content, yet Hooper’s deft directorial hand keeps the whole thing from going off the rails. Besides some tedious expository dialogue and a middle section that lags in the pacing department, Lifeforce is an incredibly watchable picture, popping with visual splendor and filled with memorable moments. Dependable British actors like Peter Firth and Frank Finlay give far better performances than is required of them, and Mathilda May has excellent screen presence given how few lines she has to say. Its characters are arch and its plot is total nonsense, but if you’re willing to buy into weapons-grade cheese, there are few movies of its type that can match the highs Lifeforce has to offer. And the secret to what’s kept it so compelling for viewers all these years later is that it’s a B-movie at heart with A-movie production craft.

Firing the Cannon

Lifeforce was one of the main attempts by Cannon Films, then known primarily for a large catalogue of cheaply produced B-movie actioners and sci-fi/fantasy films, to break into mainstream big-budget filmmaking. To that end, they courted Tobe Hooper, fresh off the box office success of Poltergeist, into a multi-film deal that started with Lifeforce. Produced on a budget of $25 million, which roughly translates to around $75 million today accounting for inflation, Lifeforce was a notable shift in production quality compared to Cannon’s usual MO. It may not have paid off for Cannon at the box office, but they had the right idea, since they did make bank with the similarly budgeted Sylvester Stallone vehicle Cobra the following year. Hooper was given considerable leeway to make the film he wanted with Lifeforce, which shows in the final product given how over-the-top it is with its violent imagery and sexual themes.

With Cannon’s financial backing, Hooper assembled an incredible group of talented creatives to fill out his crew. These included John Dykstra, who had won an Academy Award for visual effects on Star Wars, Return of the Jedi cinematographer Alan Hume behind the camera, and legendary composer Henry Mancini for the original score. And it shows in the final film, which looks fantastic for a movie from its era, with VFX and production design of a high standard and vibrant compositions brimming with color and detail. Mancini’s bombastic main theme that plays over the opening credits would be an instant classic in a more well-known film, and it’s used to great effect multiple times in the third act. Pretty much all that distinguishes Lifeforce from its similarly budgeted brethren is how insane it is.

Movies with such weird and sexually charged material, even from auteur filmmakers, are typically made for much lower budgets. Indeed, that was Cannon Films’ usual wheelhouse, and Lifeforce feels cut from the same cloth as the company’s previous efforts, or sibling low-brow favorites like the Hammer horror films of the 1950s and ‘60s, or even Roger Corman-produced sci-fi movies like Galaxy of Terror and Battle Beyond the Stars. Seeing a movie that shares its creative ethos with such enthusiastic low-budget pulp be made at such a grand scale is the kind of rare treat that feels designed in a lab to create a cult following. And despite middling reviews from critics, Lifeforce has indeed lived on with film fans, not just for its craft but also its brazen spirit.

Sex, Lies, and Vampires

The most alarming aspect of Lifeforce as it relates to the contemporary blockbusters is how you simply could not get away with making a film as unabashedly horny as this on a big studio budget today. Sure, big movies can have romance or characters expressing desire for each other in them, but that’s not Lifeforce’s game. It’s a movie defined by unrestrained lust, both in terms of the story being told and how it presents it. Sure, there’s obvious things like Mathilda May walking around naked in the Space Research Centre and her character using her body-hopping powers to seduce new victims, but it goes deeper than that. The vampires don’t use the typical blood-sucking mechanic, instead opting for draining energy directly via kisses or other close physical contact, and it’s said in dialogue that the transfer is sexual in nature, especially when the Space Girl uses her “overwhelming” feminine presence to obtain it.

Vampire fiction is almost always somewhat horny, going as far back as Sheridan Le Fanu’s 1872 lesbian vampire novel Carmilla and Bram Stoker’s seminal work on Dracula, and up through the vampires of today like Lady Dimitrescu from Resident Evil: Village or Robert Eggers’ take on Nosferatu. In Lifeforce, Hooper lives up to the trend by portraying Carlsen’s barely contained desire for the Space Girl as the driving force of not just their psychic connection, but the entire plot. That’s the crux of the revelation that Carlsen was the one who sabotaged the Churchill, and when he says that leaving her “was the hardest thing I ever did.” Carlsen didn’t stop the Space Girl from slaughtering his crew, and he still wants to be with her even when she’s blowing London to smithereens. This is a movie where a single man’s desire for an alien vampire nearly brings about global destruction. Talk about being down horrendous!

The sexual theming also extends to the vampires’ victims, which become zombie-like beings who must find new humans to drain every two hours or risk exploding into dust. If the life force transfer is sexual in nature, and the zombies must propagate the contagion constantly to not wither away, then the message is clear: “fuck or die.” It’s the operating animus that leads to London becoming an all-out Romero-style plague zone within the span of a single night, littered with corpses, burning buildings and the undead pouncing on any screaming civilian in sight to drain more life energy. The infectious death drive intrinsic to zombie fiction is given a horrifying sexual dimension in Lifeforce, one that isn’t really subverted by the finale. Carlsen does “kill” the Space Girl, but only by giving in to her and stabbing both her and himself with a giant iron sword as they nakedly embrace. They then get launched into the vampires’ ship and leave with their true fate unknown, meaning it’s possible the Space Girl got everything she wanted.

Lifeforce is a baffling film in any era, but after decades of blockbusters that have slowly shaved off many of their irregular edges for mass palatability, a movie like this only becomes more fascinating. Truly off the wall horror productions tend to max out in the mid-budgets, with recent examples including Gore Verbinski’s A Cure for Wellness, James Wan’s Malignant, or Zach Cregger’s Weapons. But for an all-too-brief moment, a director like Tobe Hooper got to make something truly unique and, quite frankly, batshit insane with the resources of a studio tentpole. If you’ve never seen it, you owe it to yourself to experience Lifeforce, a movie unlike anything we’re likely to see again.

Carlos Morales writes novels, articles, and Mass Effect essays. You can follow his fixations on Twitter.