This startup wants to clean up the copper industry

Demand for copper is surging, as is pollution from its dirty production processes. The founders of one startup, Still Bright, think they have a better, cleaner way to generate the copper the world needs.

The company uses water-based reactions, based on battery chemistry technology, to purify copper in a process that could be less polluting than traditional smelting. The hope is that this alternative will also help ease growing strain on the copper supply chain.

“We’re really focused on addressing the copper supply crisis that’s looming ahead of us,” says Randy Allen, Still Bright’s cofounder and CEO.

Copper is a crucial ingredient in everything from electrical wiring to cookware today. And clean energy technologies like solar panels and electric vehicles are introducing even more demand for the metal. Global copper demand is expected to grow by 40% between now and 2040.

As demand swells, so do the climate and environmental impacts of copper extraction, the process of refining ore into a pure metal. There’s also growing concern about the geographic concentration of the copper supply chain. Copper is mined all over the world, and historically, many of those mines had smelters on-site to process what they extracted. (Smelters form pure copper metal by essentially burning concentrated copper ore at high temperatures.) But today, the smelting industry has consolidated, with many mines shipping copper concentrates to smelters in Asia, particularly China.

That’s partly because smelting uses a lot of energy and chemicals, and it can produce sulfur-containing emissions that can harm air quality. “They shipped the environmental and social problems elsewhere,” says Simon Jowitt, a professor at the University of Nevada, Reno, and director of the Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology.

It’s possible to scrub pollution out of a smelter’s emissions, and smelters are much cleaner than they used to be, Jowitt says. But overall, smelting centers aren’t exactly known for environmental responsibility.

So even countries like the US, which have plenty of copper reserves and operational mines, largely ship copper concentrates, which contain up to around 30% copper, to China or other countries for smelting. (There are just two operational ore smelters in the US today.)

Still Bright avoids the pyrometallurgic process that smelters use in favor of a chemical approach, partially inspired by devices called vanadium flow batteries.

In the startup’s reactor, vanadium reacts with the copper compounds in copper concentrates. The copper metal remains a solid, leaving many of the impurities behind in the liquid phase. The whole thing takes between 30 and 90 minutes. The solid, which contains roughly 70% copper after this reaction, can then be fed into another, established process in the mining industry, called solvent extraction and electrowinning, to make copper that’s over 99% pure.

This is far from the first attempt to use a water-based, chemical approach to processing copper. Today, some copper ore is processed with acid, for example, and Ceibo, a startup based in Chile, is trying to use a version of that process on the type of copper that’s traditionally smelted. The difference here is the particular chemistry, particularly the choice to use vanadium.

One of Still Bright’s founders, Jon Vardner, was researching copper reactions and vanadium flow batteries when he came up with the idea to marry a copper extraction reaction with an electrical charging step that could recycle the vanadium.

After the vanadium reacts with the copper, the liquid soup can be fed into an electrolyzer, which uses electricity to turn the vanadium back into a form that can react with copper again. It’s basically the same process that vanadium flow batteries use to charge up.

While other chemical processes for copper refining require high temperatures or extremely acidic conditions to get the copper into solution and force the reaction to proceed quickly and ensure all the copper gets reacted, Still Bright’s process can run at ambient temperatures.

One of the major benefits to this approach is cutting the pollution from copper refining. Traditional smelting heats the target material to over 1,200 °C (2,000 °F), forming sulfur-containing gases that are released into the atmosphere.

Still Bright’s process produces hydrogen sulfide gas as a by-product instead. It’s still a dangerous material, but one that can be effectively captured and converted into useful side products, Allen says.

Another source of potential pollution is the sulfide minerals left over after the refining process, which can form sulfuric acid when exposed to air and water (this is called acid mine drainage, common in mining waste). Still Bright’s process will also produce that material, and the company plans to carefully track it, ensuring that it doesn’t leak into groundwater.

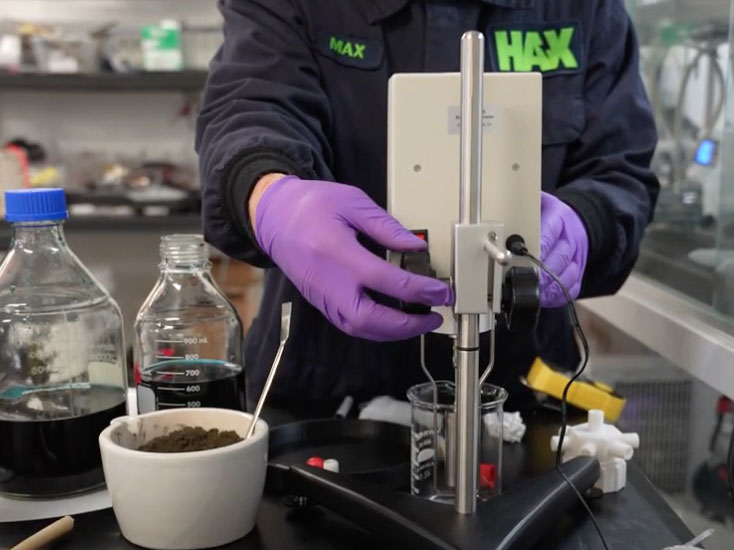

The company is currently testing its process in the lab in New Jersey and designing a pilot facility in Colorado, which will have the capacity to make about two tons of copper per year. Next will be a demonstration-scale reactor, which will have a 500-ton annual capacity and should come online in 2027 or 2028 at a mine site, Allen says. Still Bright recently raised an $18.7 million seed round to help with the scale-up process.

How scale up goes will be a crucial test of the technology and whether the typically conservative mining industry will jump on board, UNR’s Jowitt says: “You want to see what happens on an industrial scale. And I think until that happens, people might be a little reluctant to get into this.”